By Pastor Isaac Scott

America is a violent, petty nation. The people of this country call for humane justice from the highest hills, but “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” is the way this nation handles its own failures. I’ve said much in the past about the hypocrisies of the current movement to abolish prisons. Until we clearly define exactly what true justice looks like for every group of people, we will continue to see people protest against systemic oppression in the form of incarceration for some people and justify state violence incarceration as a system of punishment.

America’s go-to response, prison, is a violent monster without taste buds but with an inexhaustible appetite. The immediate emotional response when a person breaks the law is to seek out punitive responses to deter their behavior rather than invest resources and time into addressing the root causes of the issues that led to the crime. Moving toward and creating a more harm-reductive criminal legal system means that we must define accountability outside of the context of punishment. We live in a nation where the line between accountability and punishment is not clear, and because there is no distinction, the two concepts become one in their application.

The most important reason that we as a nation must abandon the punishment cycle and begin to find alternatives to incarceration for every person, especially for people who are convicted of violent crimes, is because violence only begets violence, and responding to a person who becomes violent by placing them in a violent system is a recipe for disaster. Research shows that incarceration has negative psychological effects on people, including but not limited to “a dependence on institutional structure and contingencies. Hypervigilance, interpersonal distrust, and suspicion. Emotional over-control, alienation, and psychological distancing. Social withdrawal and isolation. Incorporation of exploitative norms of prison culture. Diminished sense of self-worth and personal value. And post-traumatic stress reactions to the pains of imprisonment.” Every year, hundreds of thousands of people enter the New York state prison system and while everyone is chewed up, not everyone is spit back out into society the same way, and many are left to live with the remnants of the psychological aspects of incarceration.

Public safety can no longer be an excuse for this nation’s reliance on incarceration. Research shows us that prison does not keep us safe. We need to think outside of the box if we truly seek to identify nonpunitive methods for accountability, especially for people who commit heinous crimes. I admit: In my 38 years of life, I have seen and heard things that made me consider whether jail was the best place for people who commit certain acts. Likewise, as an abolitionist who followed the Derek Chauvin trial, I still struggle with the dilemma of navigating the emotional space between healthy accountability and retribution. While I wanted this man to be held accountable for his despicable actions, at the same time, I wouldn’t wish prison on my own worst enemy. No doubt, any time physical harm is at stake, there is a culturally responsive need for temporary separation that is time-sensitive and concerned for the well-being of all parties involved, but I do not believe that jail or prison is the separation that is needed for any form of safety prevention.

Are we seeking accountability that humanizes every person involved, or are we seeking revenge against people who break certain laws? Prison should not be the answer for addressing crime or any societal issue. Prison should not be the answer to the people that society feels are irredeemable. The deprived social environment of prison can potentially impede one’s social capacity to navigate various social obligations post-incarceration, such as employment, housing, and other family and social obligations. The secondary effects of incarceration are being emotionally ignored in the heat of the moment and rather than humanizing each person by putting resources into dealing with the roots of our societal issue, the popular pejorative fosters an out of sight, out of mind attitude and casts certain people away never to be remembered again, while others are worth giving a second and third chance. Before we remain content that we can continue to send people through this violent state apparatus, we should understand that many people do not survive incarceration and that just because a person is able to avoid being rearrested, it doesn’t mean that safety is present for that individual and that the psychological effects of incarceration are not haunting them and causing equal stress in their lives and in the lives of their families.

Recycling punishment is not the solution—prevention is. If we truly want public safety, then we must begin providing preventative harm-reductive solutions in four significant areas: first, mental health in order to prevent the incarceration of people who would benefit from medical support; second, social support and wellness in order to provide more therapeutic and intervention work with struggling families; third, educational support to foster knowledge, access, capacity, and opportunity amid difficult living circumstances; and fourth, economic support to address poverty and food insecurity. Until then, we will continue to be a nation reliant on incarceration. Preventing incarceration by addressing the socioeconomic issues that lead people to commit crimes is a leap toward human justice and the thoughtful abolition of our current criminal justice system.

--

This article is published in collaboration with the Columbia University Center for Justice, Pastor Isaac Scott, and the Columbia Spectator.

Pastor Isaac Scott is is an award-winning, Social Impact Multimedia Artist and Human Rights Activist. He is a Fellow at the Center for Institutional and Social Change at Columbia Law School and Founder & Lead-Artist for The Confined Arts at the Center for Justice at Columbia University, where he spearheads the promotion of justice reform through the transformative power of the arts. Through The Confined Arts, Pastor Scott has organized art exhibitions, poetry performances, and storytelling projects to interrogate and bring about awareness around several important issues, such as juvenile justice, solitary confinement, prison conditions, the rising rate of women in prison and the media’s role in shaping public perception. As a result of the impactful work of The Confined Arts, Pastor Scott received the 2018, 2019, and 2020 Change Agent Award from the School of General Studies at Columbia University, where he currently studies Visual Arts and Human Rights as a Justice in Education Scholar Scholar. Today, Pastor Scott holds the esteemed title of Associate Pastor at God’s Touch Healing Ministry, located in East Harlem, NY, where he serves on Manhattan Community Board 11 on the nomination of City Council Bill Perkins.

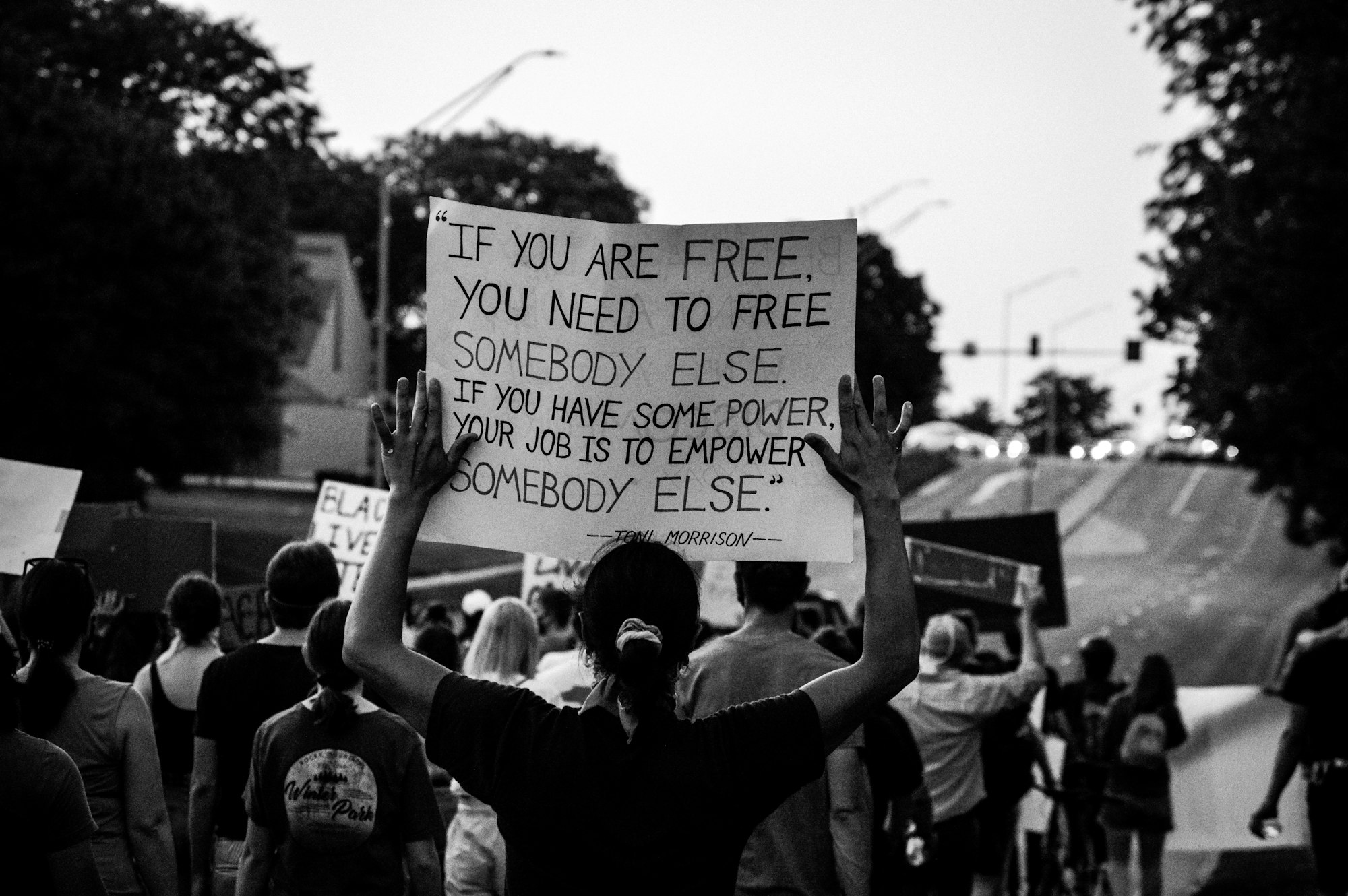

Featured image: (C) Kalea Morgan / Unsplash