The Detroit police department has always had troubled relations with the community they are supposed to be protecting and serving, but recently, that relationship has been even more strained. The police have been involved in multiple shootings in the past three months, including the shootings of two individuals who were experiencing mental health crises. After the public outcry against these abuses, the Detroit PD will soon be giving their officers new equipment such as upgraded body cameras and “less than lethal” weapons, which are designed to supposedly injure, not kill. However, until those interventions are available, the body count attributed to the DPD is rising, especially among the BIPOC community and those with mental health issues.

Detroit Police Department's Response to Mental Health, Part I: The Murder of Porter Burks

On October 2, 2022, Detroit native Porter Burks was murdered by the Detroit police while in the midst of a mental health crisis. Mr. Burks had been in and out of the hospital multiple times for his schizophrenia, and had also had multiple interactions with the Detroit police. The morning of his death, the police responded to a 911 call placed by Mr. Burks’ brother, who was concerned for his brother’s health and the safety of his community. Mr. Burks was in the middle of the street holding a knife when the police found him, and when he allegedly lunged at an officer, five officers shot him 38 times, killing him.

No mental health personnel were at the scene, though a “crisis intervention officer” did attempt to de-escalate the situation verbally. The issue at hand is that the police shot Mr. Burks so many times, with intent to kill, rather than to disable and get help for him. Even the Detroit Police Director of Professional Standards and Constitutional Policing, Christopher Graveline, admitted that the system had “failed” Mr. Burks multiple times.

Detroit Police Department's Response to Mental Health, Part II: The Murder of Ki'Azia Miller

Then, on November 10, 2022, the Detroit police responded to a 911 call made by the mother of Ki’Azia Miller, a local community member who was having what her family described as a “mental break.” Ms. Miller suffered from schizophrenia. During her mental health crisis, Ms. Miller had allegedly struck her mother and seven-year-old son, and had some weapons in the home, including a gun—but the gun was never fired. Police shot Ms. Miller four times, even though her mother was begging them not to shoot her daughter. The officers in question stated that they felt the son’s life was in danger and shot Ms. Miller to protect him; these officers were placed on administrative leave and investigated, but were later reinstated.

Porter Burks and Ki’Azia Miller were just the latest in a long line of people experiencing mental health crises who were injured or killed by the police instead of receiving help for their issues. The criminalization of mental health problems in America has a long history; police are taught to deal with these situations as dangerous ones often requiring lethal force responses. The introduction of less-than-lethal weapons designed to “take down” a person (allowing for actual mental health interventions) will hopefully lead to fewer deaths in the community at the hands of the police. Better body cameras will allow the community to scrutinize the actions of the police more closely and effectively.

But that does not bring the people who have already suffered and died back to life, for the “crime” of having a mental health problem.

A Nationwide Crisis: Police Response to Mental Illness Causes Trauma in Black Communities

This is not just a Detroit problem: it is a national one which demands a solution. At least 25 percent of the people shot and killed by the police nationwide suffer from some kind of mental health problem, according to an ongoing survey conducted by the Washington Post. A study conducted by the Treatment Advocacy Center found that people with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed during an encounter with the police. Police are not typically trained to de-escalate situations, and they have no clinical skills in assisting people in crisis.

A national “988” crisis line was rolled out in 2022, designed to connect callers with crisis prevention services. This innovative 24-hour call center fields calls from those in distress or from those seeking help for others, and then dispatches teams to respond, whether to suicidal crises or other mental health-related distress. The goal is harm reduction.

Even more troubling, Black people are three times more likely to be killed by police than white people, according to a study done by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Some research even suggests that the risk of death increases for Black people who show signs of mental illness. Both Ki’Azia Miller and Porter Burks were African Americans with schizophrenia. Neither received the proper clinical help they needed, or the support from the powers that be—when they became “problems,” the solution was the quick and fatal one, the application of bullets instead of actual help.

Black communities have historically been resistant to clinical mental health interventions, preferring to handle these issues internally, due to a distrust in a mental health system that was designed with white supremacy in mind. Things are changing, though, with the evolution of more progressive schools of thought in the fields of psychology and sociology. Community-based techniques such as direct intervention teams that work with local residents to divert mental health crises from police attention are effective harm reduction tools as well.

Reducing Harm from Police Response: Silent Cry, FORCE Detroit and Friends Host Community Healing Event

My name is Shawanna Vaughn, and I am the director of Silent Cry, Inc., a non-profit organization dedicated to criminal justice reform, gun violence reduction, advocacy, and trauma education. After the horrific shooting of Porter Burks, Silent Cry, Inc., with Pure Legacee out of Brooklyn, New York, and Rising Sun Ink out of Inkster, Michigan, got together and collaborated on a trauma response to care for the community impacted by the violence and loss. It was a great event, and much healing was done with the support of FORCE Detroit, a nonprofit focused on furthering community-based social justice efforts through conversations between interfaith, grassroots and public sector leaders. There was art therapy done by Kaylese, massage therapy and music provided by Evan and Amber, and Tia Littlejohn-Taylor was on hand to provide counseling services. Pastors Kevin Harris, Darryl Woods and Teferi Brent were also available to provide comfort and counsel to those seeking religious support. Jay Love, a popular Michigan activist on the radio show run by Sam Riddle, Political Director of the Michigan National Action Network, was also there.

It was a day to reflect and bring direct services into our neighborhoods, where Black communities do not receive trauma care. Our non-BIPOC counterparts have more resources, services and finances to address these issues of trauma and mental health, so we must address the problem directly ourselves. When Black children are affected by gun violence and shootings in our communities, they sustain trauma, which is called ACES: Adverse Childhood Experiences. ACES are not being addressed by Detroit officials.

A Call From Silent Cry: Raise Trauma Awareness Everywhere

On behalf of Silent Cry, I would like to put out a call to work with my local elected officials here in Detroit and with our state government, to bring trauma awareness to every community. Healing begins before the bullets start, because waking up in abject poverty is already creating trauma and mental health issues which play out in schools and on our streets. We have to address these problems in our community now.

Mental illness and the adverse effects of trauma should not be a death sentence. Detroit Police Chief James E. White is working to improve the response and training to help law enforcement assist in mental health crisis calls and not turn them into fatal shootings, addressing this with new equipment, mental health first aid and special officers to handle the calls. Bringing in stakeholders to interact with the department is historic and vital to repairing communities and making Detroit strong. We are here to support our communities.

If you would like to support the work of Silent Cry Inc., click here for our donation link. We are seeking sponsorship for mental health conferences in 2023, with one in Detroit and another in New York. Sponsorship information is available on our website, silentcryinc.org.

Find Out More On Social

--

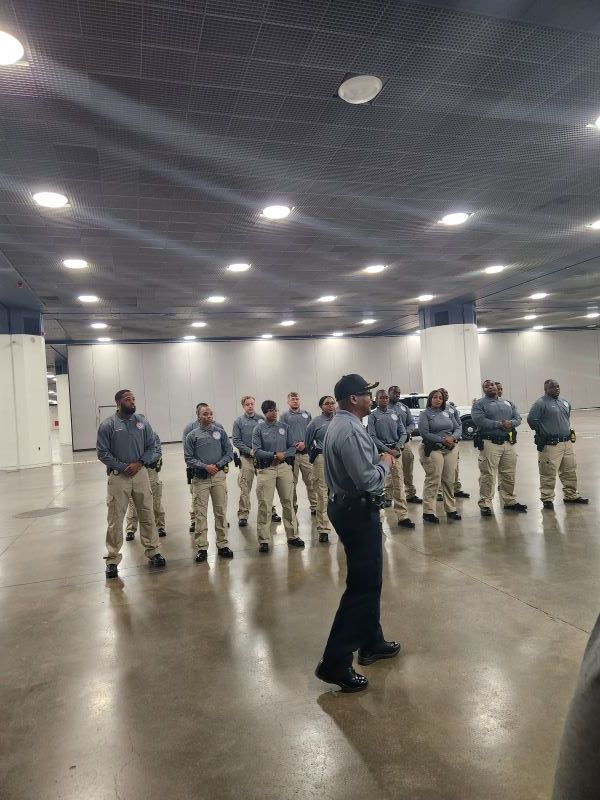

Featured image: Community leaders gather at the Silent Cry and FORCE Detroit event for mental health, including pastors Kevin Harris, Darryl Woods, and Teferi Brent. (C) Silent Cry Inc.