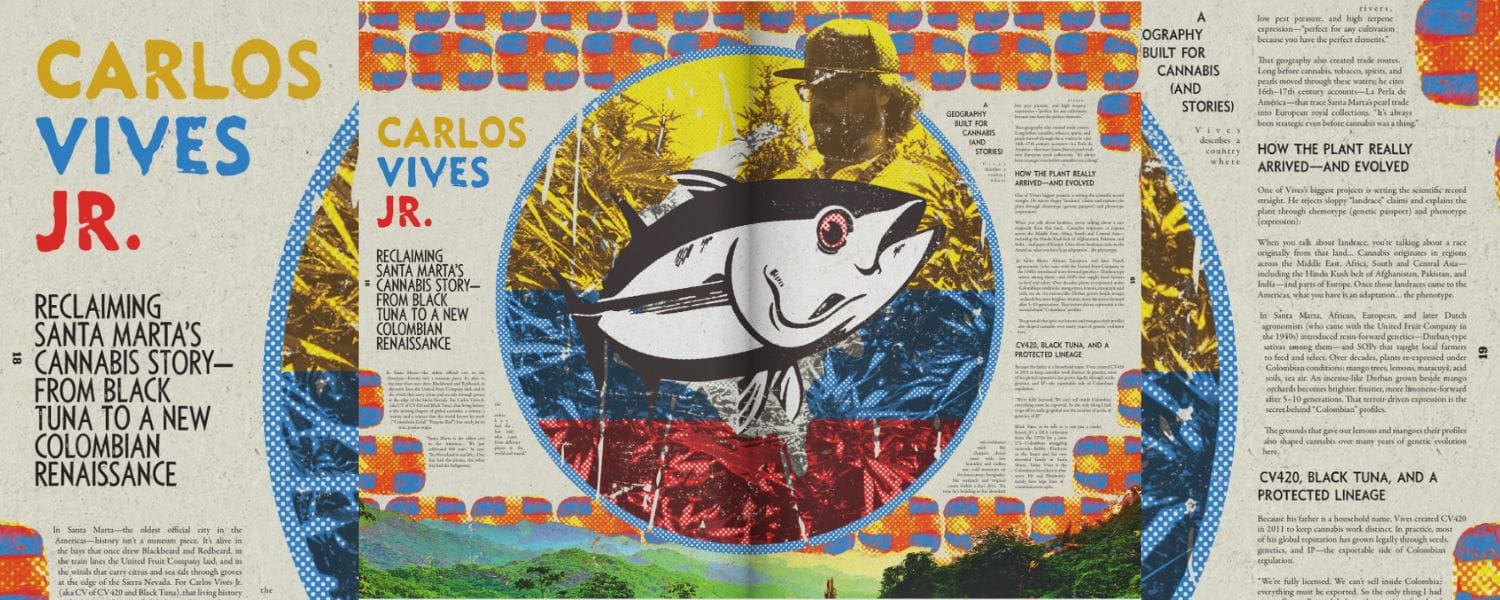

In Santa Marta—the oldest official city in the Americas—history isn’t a museum piece. It’s alive in the bays that once drew Blackbeard and Redbeard, in the train lines the United Fruit Company laid, and in the winds that carry citrus and sea salt through groves at the edge of the Sierra Nevada. For Carlos Vives Jr. (aka CV of CV420 and Black Tuna), that living history is the missing chapter of global cannabis: a culture, a terroir, and a science that the world knows by myth (“Colombian Gold,” “Panama Red”) but rarely by its true, precise origin.

“Santa Marta is the oldest city in the Americas… We just celebrated 500 years,” he says. “It’s Neverland in real life… One bay had the pirates, the other bay had the Indigenous, the other bay had the lost kids who came from different places in the world and stayed.”

A Geography Built for Cannabis (and Stories)

Vives describes a country where microclimates stack like chapters: desert oases with low humidity and endless sun; cold mountain air five hours away; Everglades-like wetlands and tropical coasts within a day’s drive. The zone he’s building in has abundant rivers, low pest pressure, and high terpene expression—“perfect for any cultivation because you have the perfect elements.”

That geography also created trade routes. Long before cannabis, tobacco, spirits, and pearls moved through these waters; he cites 16th–17th century accounts—La Perla de América—that trace Santa Marta’s pearl trade into European royal collections. “It’s always been strategic even before cannabis was a thing.”

How the Plant Really Arrived—and Evolved

One of Vives’s biggest projects is setting the scientific record straight. He rejects sloppy “landrace” claims and explains the plant through chemotype (genetic passport) and phenotype (expression):

When you talk about landrace, you’re talking about a race originally from that land… Cannabis originates in regions across the Middle East, Africa, South and Central Asia—including the Hindu Kush belt of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India—and parts of Europe. Once those landraces came to the Americas, what you have is an adaptation… the phenotype.

In Santa Marta, African, European, and later Dutch agronomists (who came with the United Fruit Company in the 1940s) introduced resin-forward genetics—Durban-type sativas among them—and SOPs that taught local farmers to feed and select. Over decades, plants re-expressed under Colombian conditions: mango trees, lemons, maracuyá, acid soils, sea air. An incense-like Durban grown beside mango orchards becomes brighter, fruitier, more limonene-forward after 5–10 generations. That terroir-driven expression is the secret behind “Colombian” profiles.

The grounds that gave our lemons and mangoes their profiles also shaped cannabis over many years of genetic evolution here.

CV420, Black Tuna, and a Protected Lineage

Because his father is a household name, Vives created CV420 in 2011 to keep cannabis work distinct. In practice, most of his global reputation has grown legally through seeds, genetics, and IP—the exportable side of Colombian regulation.

“We’re fully licensed. We can’t sell inside Colombia; everything must be exported. So the only thing I had to go off to really go global was the creation of seeds, of genetics, of IP.”

Black Tuna, as he tells it, is not just a catchy brand; it’s a DEA codename from the 1970s for a joint U.S.–Colombian smuggling network—Bobby Platshorn in the States and his own extended family in Santa Marta. Today, Vives is the Colombian lineal heir to that story. He and Platshorn’s family have kept lines of communication open.

“We showed him all of our papers here in Colombia… I had the honor of talking to Robert before he died… We went back and forth on places, names, runways. It tied the story together.”

His vision for the U.S. is pragmatic: either co-develop Black Tuna stateside (“half and half”) and modernize it with new genetics, or proceed as Carlos Vives/Black Tuna for the rest of the world while keeping respect for the U.S. IP.

Proof, Receipts, and the Elders

Vives is obsessive about historical verification. He points to Uncle John of Cutting Edge Solutions—a 60-something California/Oregon/New York OG—as a living archive who connects the Haze Brothers to Santa Marta material in the late 1970s.

“I’ll ask, ‘Do you think this is Santa Marta Gold?’ He smells it and goes, ‘Holy f*** — that’s what I smelled when I was 18 when the Haze Brothers brought it from Colombia.’ That’s when I know we’re on the right path.”

Together, they co-founded the Caribbean Cup in Santa Marta—an invitational for flower, hashmakers, and global brands designed to re-anchor Colombia among the world’s cannabis capitals (Amsterdam, Morocco, Barcelona, Thailand, California).

Chemistry Over Hype: The Anxiety Problem

Vives is blunt about modern retail pitfalls: distillate at 90% THC with reconstituted or fake terpenes.

“You’re opening up receptors you might not be able to handle… If you have the terpenes that direct the cannabinoids, then you direct it to different receptors… But distillate with fake terps? You’re going straight to the brain.”

He prefers full-spectrum, terroir-driven resin where the native terpene ensemble orchestrates the effect—sedation, euphoria, creativity—without the panic switch.

The analogy he loves is coffee: Colombia grows some of the world’s best, but industrial espresso culture masked its nuance for decades. The first time he had properly extracted filter coffee, he tasted blueberry notes for real. Cannabis is the same: get the variables right, and the plant delivers its symphony.

Culture as Compass, Not Costume

Black Tuna is storytelling, yes—but it’s not marketing cosplay. For Vives, culture guides compliance, genetics, and tourism:

- Compliance & Export: Three licensed facilities; state-of-the-art greenhouses; millions of registered seeds; a legal framework that prioritizes export and IP.

- Genetic Program: Long-term selections preserving true Santa Marta expressions verified by elders and history.

- Tourism & Education: Plans to host deep-history tours: mountainside groves, hidden runways, fishermen’s docks, and oral histories from octogenarian workers who lived the 1970s.

“There are a thousand cannabis companies—but many ran out of stories. I want to see how many grow in one of the capitals of the weed world.”

On Big Pharma, Investment, and Pace

He’s cautious about outside capital that warps mission.

“If your company can’t make its own money and grow naturally, then you shouldn’t even exist… The investor will change your plastic, your inputs, your soul. In cannabis, that’s dangerous.”

Colombia already saw the Canadian capital wave—and its retreat. His approach: organic scale, patient legality, and global partnerships that respect origin.

Five Years Out

“We’re known by the industry. Now we go to the world.”

The plan:

- Expand genetic distribution to growers who want to start from seed with provenance.

- Grow the Caribbean Cup into a must-stop on the global circuit.

- Build cannabis tourism that connects Brazil → Colombia → Mexico → California as one continuous story of the plant’s American journey.

- Explore a U.S. alignment for Black Tuna that honors both sides of the legacy.

Why This Matters Now

Amid rescheduling talk in the U.S. and medical expansions in Europe, origin and accuracy are currency. If the future of cannabis is pharmacovigilance plus terroir, Santa Marta’s story sits at the center: a place where the plant adapted honestly—and where a new generation is finally telling that story with receipts, regs, and resin.

“Everything’s already been invented,” Vives quotes his father. “The formula I chose has been invented in other countries: they protect their hash, their history, their books. We just hadn’t told ours. Now we are.”

For more, visit https://blacktuna.com.co and Instagram.