I backtrack in my mind and finally get a fix on the confrontation that happened when I was about to begin my second-grade year at St. Denis . . . It was in the month of August 1966 and I was at Mass with Dad listening to Father Bartholomew give the sermon. That weekend, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came to lead different parts of Chicago on behalf of the Chicago Freedom Movement and their Open Housing Marches. . . and I could never forget how an angry parishioner stood up at the back of the church and started screaming at Father Bartholomew.The guy was ranting because Father Bartholomew had been speaking about how King was fulfilling a mission and that he was not just Dr. King but also the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King.Father Bartholomew spoke about how King’s search for “justice and equality for the Negroes” was ours to think about; and to be open-minded, too. Well, the back row screamer let loose with a slew of endless insults and foul words. He must’ve gone on for at least one full minute before two of the ushers, in their bronze-colored sport-coats with the unique crests on the front of their jackets, finally got to him by entering his pew from both sides, grasping him by the elbows, and escorting him out of the church. It was astounding. The Open Housing Marches that had enraged the man were the same ones that had so recently caused major crowds to turn out violently at Marquette Park right near our house, and also Gage Park a bit farther away, and also right over by Bogan High School.Cars had been attacked and set on fire; marchers were even stalled or turned back by the police, because the bottle-throwing and brick-throwing and knife-throwing were so out of control. And yet, to the back row screamer, the message of reconciliation Father Bartholomew wanted to preach was even worse than what “they” wanted. “They” were constantly referred to in his screeching as “those niggers” and “those niggers were agitators” and “those agitators” counted on “nigger-lovers like you Father.” Every time he yelled out the word Father, he’d point at the altar and straight at Father Bartholomew, who stood quietly at the lectern while this guy called him “a no-good-nigger-lover.”The gasps and the head-turning astonishment were everywhere. After the furious man was ushered out, the sermon continued as though nothing had happened. Father Bartholomew never shouted back; he didn’t insult the man or say anything negative.Later, Dad explained to me what all that yelling was about and I had a keen understanding of it because the day before or the week before, on a Saturday, I’d gone with Dad not knowing the exact nature of what I was about to see. But what I saw was the leftover debris of the Marquette Park riot that exploded when Dr. King led a march right through the heart of my Grandfather’s neighborhood, and according to Dad four thousand members of the Chicago Police Department had to be there to try to protect King and his Chicago Freedom Movement marchers.I also learned that the real reason Dad wanted to go look around Marquette Park that day was because he was worried about the violence spilling right across 71st Street and affecting his parents’ home at 7119 South Sacramento. That’s why we checked in with my Grandfather at the big old brownstone and all was okay. It may have been for the best (even though she was really sick) that Grandma Mary Clare was back in the hospital, so she didn’t have to look out her front door and see Marquette Park turned into a warzone.That’s what it resembled when Dad and I took a walk through the park and I couldn’t believe that right in the same lagoon where we’d always fed the ducks and watched the Sunday morning mini-motorboat races, when weather permitted, there was a blue Dodge that’d been shoved into the water after some of the locals dragged “the Negroes” out of it and beat them until the police stepped in. The car was obviously ruined and its rear bumper and part of the trunk stuck out of the water. I could see the Dodge symbol on the rear of the car.The march was over and King was gone by the time Dad and I walked through Marquette Park. But the aftermath was obvious; shattered glass lay everywhere; cars once driven by citizens who’d come to witness or join in the march had been stopped, bashed, ransacked, the occupants forced out . . . and that’s why I saw three different overturned cars that were still smoldering after being set ablaze.Firemen were all over, spraying and squirting, and Dad was out of his mind with anger when passersby told him that the firemen had a real problem earlier: Some of the teenagers from the white gangs who were completely caught up in the bottle-tossing and the brick-throwing, had also whipped out knives large enough to slash through the firehoses uncoiled on the ground . . . and when the firemen had tried to hose down the various cars that had been set on fire, some of the hoses were suddenly useless. It made everything even more dangerous and all I ever heard Dad say was that the policemen and the firemen were there to help us; so the idea of anyone hurting them was unthinkable. But now it wasn’t just locals talking.Uncle Burton caught up with us right across the street from the Grandfather’s house. He wasn’t really our uncle, and yet he was, because he and Dad had been great friends since the mid-1950s. Dad worked at Burton’s father’s clothing store down on 63rd Street and Burton’s father, Mr. Jerry Cohen, (we called him “Mr. J.”) got Dad his first job at Kuppenheimer many years earlier. And though they were Jewish friends, Burton and his wife Lois were called “Uncle” and “Aunt.” They were always calling my Mom.They visited our house on 85th Street sometimes, and on other occasions we went to their house. Uncle Burton had called my Mom and she told him we were at my Grandfather’s, and that wasn’t more than a mile from the Burton’s Store for Men where Dad got his start in the clothing industry (I wondered if Dad would name a store after me the way Mr. J. named his store after his oldest son).

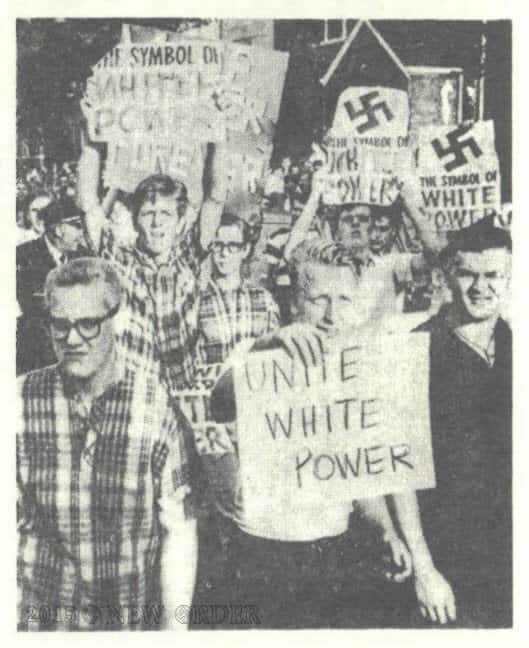

Uncle Burton found us easily and I listened as he and Dad talked about what was happening. I could see how mad they were. And I knew it wasn’t “the Negroes” or Dr. King they were mad at; they kept shaking their heads and pointing at broken glass and smoking automobiles in the near-distance, and I knew that they were outraged by the neighborhood rioters. Dad kept telling Uncle Burton that thousands of policemen had to be there and still King and his marchers were hit with so many bottles and bricks and rocks and stones and even a knife or two thrown right at him . . . that the policemen had also ducked left and right, to shield themselves from the mob’s fury.Many subtleties were lost on me. But the obvious was there to be heard and seen and I saw expressions of disgust on Dad’s face and something stranger, something heartsick, on Uncle Button’s face as several passing cars and also pedestrians were brandishing posters or flags with the words WHITE POWER printed right below the Nazi swastika, which was printed big or spray-painted and displayed all around us.–(M. J. Moore is Honeysuckle Magazine’s RETRO columnist. This piece is excerpted from his memoir-in-progress, It Don’t Come Easy ~ A Boyhood in the Aftermath of the 1960s. Moore’s novel, For Paris ~ with Love & Squalor, will be published in October by Heliotrope Books.)