By Shawanna Vaughn and Michelle Mason

In need of a life-saving bone marrow transplant for leukemia and positive for COVID, DeReta Steverson, incarcerated at the California Institution for Women (CIW), is still not eligible for compassionate release in California, even under the state’s much-hyped release program.

Having served 22 years of her sentence, Ms. Steverson is parole-eligible. But, instead of being released, she is accruing medical debt and continues to be traumatized by the healthcare she does receive; from denial of treatment to being shackled while receiving chemotherapy.

Ms. Steverson is not alone in her experience with the inhumane prison healthcare system.

As we continue to reveal more about our country’s racial injustice and the abuse Black Americans endure at the hands of law enforcement, the current pandemic has shed some light on the healthcare and human rights crisis that lives behind barbed-wire fences and concrete walls. Long before COVID, our prison system has been carrying out egregious abuse and violations of our most vulnerable citizens through inadequate, neglectful, and ultimately deadly healthcare conditions.

Shawanna Vaughn, the founder of SilentCry, first met Ms. Steverson when she was incarcerated in the early 2000’s. Through her advocacy and organization, Ms. Vaughn is taking on the prison healthcare system, advocating for Ms. Steverson among several others. After introducing her Post-Traumatic Prison Disorder Act to multiple state legislators, she is turning her attention to drafting a “Health Justice” bill that seeks to address the inadequate medical care of incarcerated individuals. The bill would ensure incarcerated individuals have a full range of mandatory exams and screenings, access to Medicare and Medicaid, and holistic health care resources, as well as improve overall care and conditions.

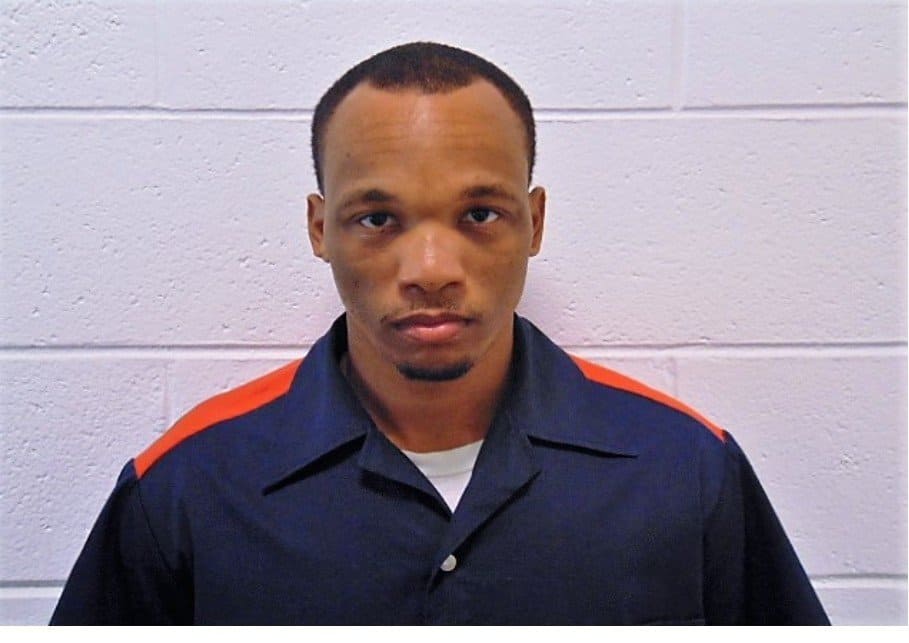

Quentin Jones, who developed hypertension over 22 years of incarceration in Michigan Prisons, is another of Ms. Vaughn’s cases. Despite being considered a chronic care patient, Mr. Jones was denied medical treatment after complaining about chest pain and shortness of breath. It usually takes at least a week for him to be seen by a nurse. This particular time, it took three months.

After finally being accepted for medical care, Mr. Jones was told his pain was due to the mask he’s required to wear because of the pandemic. He was sent back to his unit and charged $5 for his visit. To put it in perspective, Mr. Jones makes $8 a month for working while incarcerated. He often debates if he should seek medical care or purchase essentials like soap and toothpaste.

Despite suffering from his own ailments, Mr. Jones tries to help his friend, Elijah Robinson, who is experiencing even worse neglect. Mr. Robinson has a urethra kidney stent that must be changed every three months. He has not been taken to get it changed since June 2019.

This past May, Mr. Robinson began experiencing severe pain and found blood in his urine. After finally being taken to the infirmary in June, he was told that because of COVID his problems were “non-essential.” He was finally sent to an offsite clinic in early July. Upon his arrival, he was informed that the clinic did not perform the stent replacement. Mr. Robinson is grieving the process and has yet to receive proper care.

While some are denied care, others experience overzealous or dangerous medical care.

“You either receive no treatment or are subject to weird experimental tests and treatments,” said Anastazia Schmid. Ms. Schmid was incarcerated for 18 ½ years in Indiana women’s prisons. When she was first sent to jail, awaiting trial for over a year, she was immediately put on a cocktail of medication. When she was convicted and sent to prison, the doctor who performed her introductory examination discovered she had toxic blood poisoning from those medications. Ms. Schmid was informed that she would have died if she was on the medication for another month. It took her a few years to recover from the adverse effects.

Ms. Schmid’s first few medical experiences led her to become wary of seeking prison healthcare. After watching her friends return maimed from surgeries and medical procedures, some not returning at all, she only sought medical care in dire emergencies. Similar to Mr. Jones and Mr. Richardson, Ms. Schmid was denied full medical examinations. Every year, around an individual’s birthday, the prison providers perform a physical. The quality of care is typically limited to a simple vitals evaluation, rarely including important cancer screenings.

Upon her release last year, Ms. Schmid went to a general practitioner to look into the many medical issues she had endured. She pointed out a strange spot that had been on her shoulder for years, prompting her doctor to send her to various specialists who ultimately diagnosed her with basal melanoma. She started chemotherapy last month.

What happened to Ms. Schmid, and what is happening to Ms. Steverson, Mr. Jones, Mr. Robinson, and millions of other citizens who are housed in our correctional facilities begs the question: is this treatment legal or constitutional?

In 1976, the Supreme Court ruled, in Estelle v. Gamble, that it is considered cruel and unusual punishment, an eighth amendment violation, if prison personnel act with “deliberate indifference” to illness or injury. But, the decision fails to define the line between the constitutionality of different medical responses, leaving unclear whether time, level of care, or the occurrence of a pandemic can alter the definition of “cruel and unusual.” The ruling found that failing to run certain tests or take certain measures may not be an issue of constitutionality, but of medical negligence that can be adjudicated in state court.

Further, a 1994 ruling, Farmer v. Brennan, sought to define exactly what qualifies as deliberate indifference. Eighth amendment evaluations require a subjective inquiry into the state of mind of the officials who are inflicting the punishment. This requires evidence of reckless behavior, such as failing to treat individuals who report health concerns, but it cannot be fully satisfied unless culpability is proven, like an official knowing the risk at hand – or being ignorant to the obvious risk – and refusing to provide medical care.

Though costly and strenuous, legal remedies – such as civil lawsuits or petitions for a Writ of Habeas Corpus – are necessary and available for our incarcerated population, Ms. Schmid, Mr. Robinson, and Mr. Jones deserve to gain relief for their inhumane treatment. People are suffering and dying in prison and there needs to be a radical change that prevents these violations in the first place.

For Ms. Vaughn, change begins by calling for the compassionate release of incarcerated people with critical conditions. Ms. Steverson is terrified of dying in prison due to her inability to get proper healthcare. As a country, we need to ask ourselves if we believe a prison sentence should result in a death sentence?

Currently, in New York State, there are bills to address women’s correctional healthcare and evaluating the parole eligibility of the elderly. Still, none include the amount of to the radical change Ms. Vaughn is seeking through her “Health Justice” Bill.

“Despite what crimes one may or may not have committed we are still human beings and we should be treated as such…PLEASE HELP US! I don’t want to die in prison from medical neglect.” (From an email from Mr. Jones.)

The conditions in our jails and prisons go against the values of sufficient punishment and rehabilitation that was intended. We can no longer remain ignorant of inhumane treatment in our prison healthcare system.

Shawanna Vaughn is a Criminal Justice Reform Advocate who fights hard for the incarcerated through Silent Cry Inc.

Michelle Mason is the Policy and Operations assistant for the Institute for Innovation in Prosecution at John Jay College.

We urge readers to assist this essential cause. Please contact the Michigan Bureau of Health to petition for Elijah Robinson. Please fill out this survey for the compassionate release of DaReta Gail Stevenson.