Big Tobacco is already in cannabis. They might not be splashed across the front of jars or dispensary menus, but their fingerprints are everywhere—on R&D labs, vapor devices, policy committees, and investment portfolios. They’re not coming; they’re here. And the smartest move for the industry now is to understand where they’ve set their roots, anticipate how they’ll shape supply chains, and define the standards the culture actually wants to live with.

For decades, tobacco companies have had their eyes on this space. Internal memos from the 1970s show executives sketching out ideas for “future marijuana products,” long before legalization was imaginable. They simply had to wait for the world to catch up. Canada cracked the door first, creating a federally legal sandbox where multinational tobacco firms could experiment under the banner of “research and innovation.” From there, investment poured in, paving the way for today’s corporate presence in cannabis.

Now, in 2025, they’re not just talking about joints—they’re talking about inhalation technology, medical devices, and “wellness” platforms. In other words, they’re building the infrastructure for scale. British American Tobacco has invested more than $120 million in Organigram, taking nearly half ownership and developing next-generation vapor products.

Altria, the parent company of Marlboro, spent $1.8 billion for a stake in Cronos Group, buying its way into the boardroom.

Imperial Brands committed $123 million to Auxly Cannabis, calling it a “partnership in innovation.”

Philip Morris International is in talks to acquire Israel’s Syqe Medical, known for hospital-grade, precision-dose inhalers.

Reynolds, BAT’s U.S. arm, has stayed away from direct plant contact for legal reasons but is clearly positioning itself for a “non-combustible future” of wellness products.

Each company describes its work as research, science, or compliance—and to some extent, that’s true. They bring tight quality controls, global logistics, and regulatory expertise. But it’s also about influence: owning the narrative and the supply chain before anyone else can.

There are positives to this kind of involvement. Tobacco companies understand scale: compliance systems, age verification, GMP-grade production, and product consistency. For regulators, that level of control looks like the Holy Grail. Yet scale can also flatten culture.

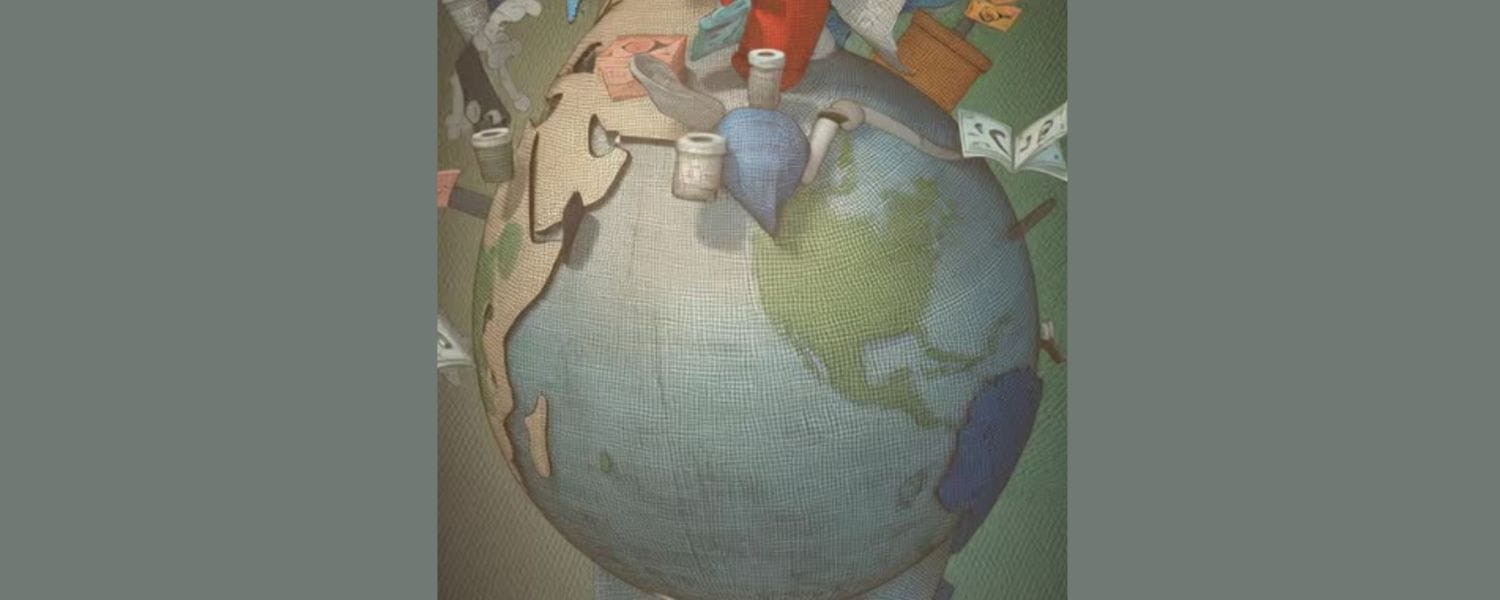

When billion-dollar corporations decide what counts as “best practices,” small growers, craft brands, and equity operators often get pushed—or legislated—out of the picture. The issue isn’t whether Big Tobacco should participate, but how they enter, who they work with, and what standards they enforce. The community’s challenge is to make growth mean progress, and integration, not erasure.

Craft and independent operators face structural challenges as the industry matures. Large-scale compliance costs, testing requirements, and distribution standards often favor companies with deeper capital reserves. In this environment, smaller producers and local brands can find it difficult to compete.

Regulatory frameworks continue to evolve, with some regions exploring mechanisms to balance market access—such as scaled compliance fees, technical support for testing, and small-business development grants. These approaches aim to maintain diversity in production while ensuring safety and consistency for consumers.

Quality standards are also expanding beyond potency metrics. Increasingly, regulators and consumers are considering factors such as sourcing, environmental impact, and transparency in production methods. The industry’s definition of “best practices” now includes traceability, sustainability, and community accountability alongside laboratory precision.

Decision-making about these standards takes place within regulatory agencies, advisory boards, and public hearings. Participation from cultivators, manufacturers, and consumer representatives helps shape how compliance and quality are defined at the policy level.

Some of these corporations may genuinely want to help establish cleaner and safer supply chains. BAT and Organigram describe their collaboration as a “platform for innovation.” Imperial Brands promotes “science-driven products.” Philip Morris points to medical precision as its north star. If these companies want to define best practices, that’s fine—but the community must be part of defining them too. “Best” can’t simply mean “corporate.”

Big Tobacco’s entrance into cannabis marks a turning point. The challenge isn’t to keep them out—it’s to make sure the culture doesn’t get erased in the process. This next chapter is about balance: preserving legacy values while demanding transparency, sustainability, and fair access for all. If these multinationals are serious about doing things the right way, they’ll prove it by partnering with and investing in the people who built this industry from the ground up. GMP standards, product consistency, and global logistics are part of the next phase of maturity. But structure without soul is control. The opportunity isn’t spending energy trying to stop what's inevitable—it’s in steering it.