It is a chilly fall morning in the South Bronx when I meet him outside his studio in an industrial area known as Port Morris, a neighborhood that’s been around since the early 1800s. Once in decay, Port Morris has turned itself around, rallying behind a FedEx headquarters, Fresh Direct, and over a dozen local businesses, interrupted by CSX train tracks, along the East and Harlem Rivers. There’s an art here, in this place where the years have degraded through the buildings—the buildings fought back.

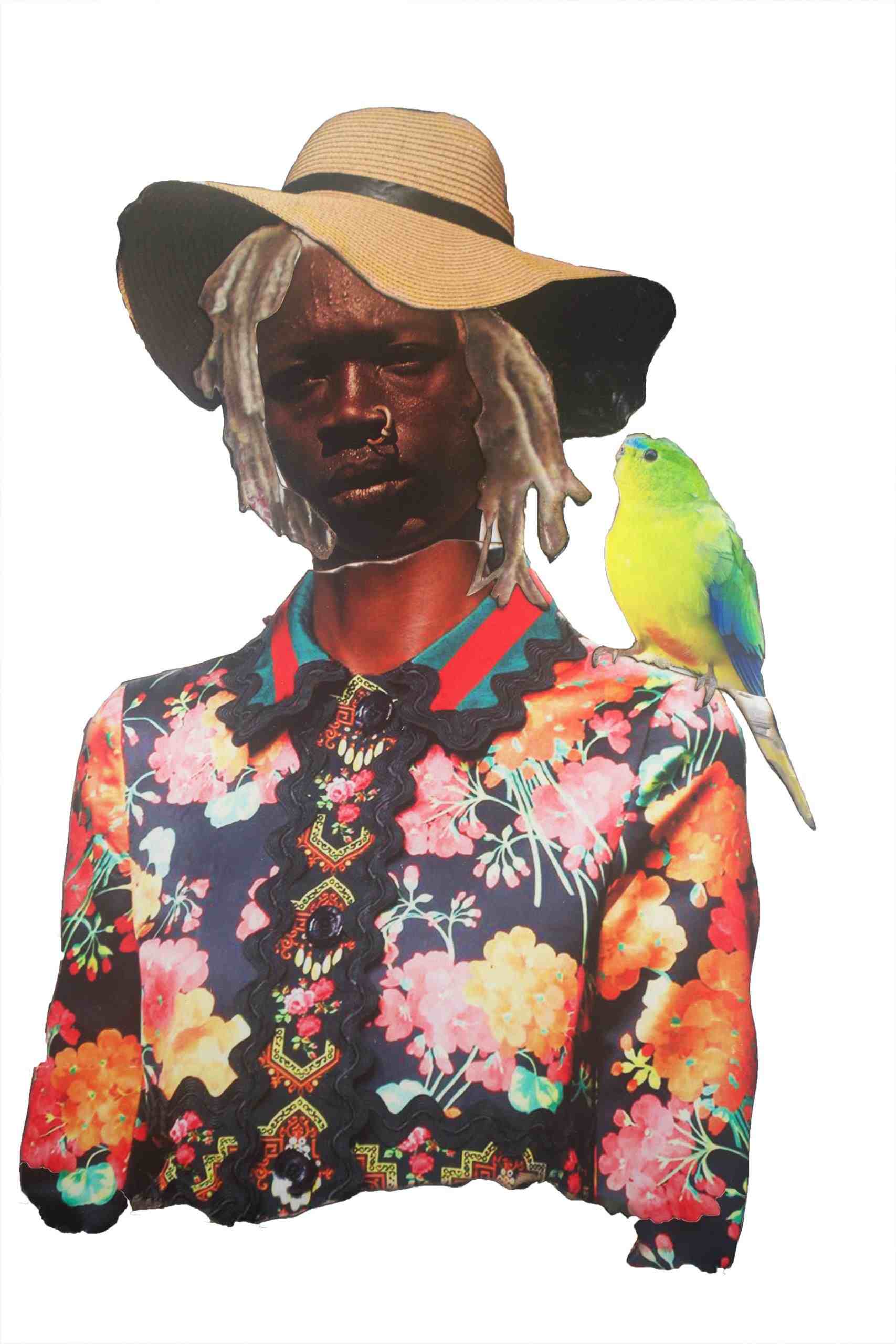

He wears a dark jacket, dark jeans, oxblood boots, and the coolest ash-gray flat ivy cap I’ve ever seen. Even his clothes are a work of art. He reminds me of Malcolm-Jamal Warner and Donald Glover, and he’s no less brilliant. Stan Squirewell instantly becomes my friend when we learn the two of us have a closer connection than either of us knew: my father. He admired, and helped ship out, prints of my father’s work as a young man in DC.

STAN SQUIREWELL: I was shipping all the prints out. That was how I got into the business of the art world. The company was called Things Graphics and Fine Art. I used to roll up your father’s work and ship it all over the country. Matter fact, we shipped internationally. I know I rolled up more than a thousand of Charles Bibbs’ pieces. I know, probably the same for your father’s pieces. Yeah, it was everywhere.

ALEX MILLER: Wow. This is just uncanny!

SS: Yeah. Before that, I was just like, ‘How do artists make money off this? This shit is impossible.’

We both laugh our heads off.

I’m from DC. Went to an arts high school, one of the first in the country: Duke Ellington School of the Arts.

Since there are a lot of different art markets, I didn’t know which one I would go for. Would it be the black fine arts market? Or was it gonna be the commercial graphic art thing? Or interior art? So many options. In the end, I just charted my own path, did a combination of all.

By the time I was 22, 23, my paintings were selling real well. I had flunked outta undergrad. That was the worst and the best thing that happened to me… going to an art high school for three years prepared me for the art world. I’d go on to meet and be inspired by David Driskell, Lou Stowall, AfriCOBRA and so many others.

AM: You’ve experienced your own art getting stolen? Happened to my dad a lot.

SS: It happens. Yeah, it really does. There’s something about the term “black,” that is very narrowing. It limits the scope of my history and genealogy. But the term does embody a certain level of importance. What I’ve discovered over the past 15 years or so…my ancestors didn’t come over on a boat. They called themselves different things around the country. My ancestors called themselves Cherokee.

My work sheds light on “global blackness”… indigenous things around the world. Academia projects the slavery narrative, but blacks have been on this side of the world for thousands of years.

Art means a genius level creativity of the mind. In any coup d’état, it’s always the artist who get X’ed out first. Why? Because the artist are the thinkers. We motivate people to change.

AM: That’s a really great point. You know how people always say things like, “black people created jazz, hip hop, and rock and roll.” But you don’t often hear about the influence we’ve had on modern art. Have you ever heard someone talk about that?

SS: (Laughs heartily) There is nothing that exists without us. Point-blank. No civilization started without us. In modern civilization, just from a genome perspective, we are a credit to everything that has happened in this world.

AM: In a previous interview, you talked about how you can see music in art. I have always wondered how to explain that. It’s like, with Ernie Barnes, you can look at that work and—that’s jazz! There’s this feeling of movement in the elongated appendages. Almost like a tempo. I don’t know how to say it, but you can just see it.

SS: Yeah, absolutely I get what you mean. My work—if I had to compare it to a specific genre, I would say it would be classical hip hop. I’m sampling and recreating, in the same exact manner that they did. I’m crate-digging in the museums. That’s exactly what I’m doing. I’m fusing things together.

What I learned is that musicians and artists think from the same part of their brain. Where I see color, they hear sound. Every color has a frequency. Every frequency has a sound. But they’re all rooted in vibration. It’s all vibration. It’s all vibes.

Too many people don’t nurture talent when they see it…or hear it. And this is how you get a society of people who look up to free-thinkers, because most people are too closed-minded to create.

Majority of the people I grew up with who didn’t have creative outlets lived very mundane lives. My mom never tried to make me “normal.” I was six when I started drawing.

AM: Amazing! What do you think about the future of black art…where will it go from here?

SS: Black art will only become more valuable and more important to society in general. My concern is whether it will stay in the hands of people in the Community. I fear that the only time the following generations will be able to look at the works their ancestors created is through the lens of a museum, or in a movie, or from a book. That is a true injustice.