Police officers fatally shot Amir Locke in the chest within ten seconds of entry into the apartment. He had no criminal record. Before he died, he had been in the process of starting a music business with dreams of eventually becoming a hip-hop artist. Amir Locke loved his family and wanted to move to Dallas to be closer to his mother. His funeral, attended by Al Sharpton, was held on February 17th. He was twenty-two years old and had not been named in the search warrant whose execution killed him.

The SWAT team of Minneapolis had been carrying out a “no-knock” search warrant related to an open murder case in the area. Though the St. Paul Police Department had originally filed for a “knock-and-announce” warrant, the Minneapolis police, who were assisting in the case, had refused to serve the warrant unless it was no-knock. Following Amir Locke’s death, the Mayor of Minneapolis, Jacob Frey, placed a moratorium on both the request and execution of no-knock warrants in response to public outcry. On April 6th, the District Attorney’s office announced that they had declined to press charges against the officer responsible for Locke’s death.

The history of the no-knock search warrant is short but bloody. With every tragic death they inspire, op-eds proclaim their end at every major news organization. ‘Does Amir Locke’s Death Mark the End of the No-Knock Warrant?’ countless articles ask, and there is no answer to their question. Breonna Taylor’s death was not the end, nor was Karhyn Johnston’s, nor were the deaths of countless others before and after them. The list of dead and injured goes on and on, yet little has changed since the first issuance of the no-knock search warrant.

What is a No-Knock Warrant?

Search warrants are such an important part of civil life that they are provided for under the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution, which protects citizens from unreasonable searches and seizures, stating that, “no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

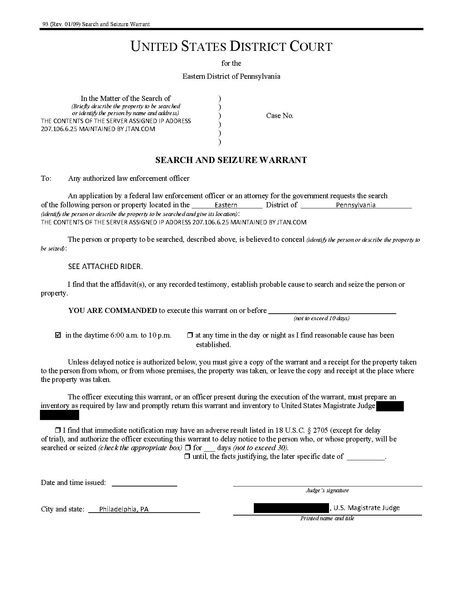

A search warrant is granted based on probable cause and must be specific in describing the place or places where a search is to take place, the things law enforcement is looking for, and the window of time in which the warrant will be executed. Another general rule of search warrants is that police are required to make their presence known and indicate that they are going to conduct a search. These are called “knock-and-announce” search warrants.

A no-knock search warrant is, essentially, exactly what it sounds like. This type of search warrant is an exception to the knock-and-announce rule. It allows both federal and local law enforcement to enter a property without declaring their presence or purpose prior to entry. No-knock warrants are most often granted in instances in which the objects of the search would be easily disposed of or destroyed before police can enter the property and seize them. No-knock warrants are also granted in circumstances where a prior warning might cause harm to befall civilians or law enforcement personnel.

When police submit a request for a no-knock warrant, they must provide evidence that one or both of the above situations may occur. Importantly, even if a no-knock warrant has been approved, police are not allowed to execute said warrant if “reliable information clearly negat[es] the existence of exigent circumstances.” Suppose a situation ceases to be dangerous to individuals or to the integrity of evidence. In that case, police must announce their presence and intent before entry, foregoing the no-knock procedure even though it was technically granted.

A Brief American History of the Search Warrant

In 1958, the Supreme Court case, Miller v. United States, set landmark legal precedent by requiring police officers to announce their presence and intent before making a forced entry, marking the beginning of knock-and-announce search warrants. This procedure posed a large obstacle to United States law enforcement as they sought to combat the “war on drugs”. Narcotics raids, it was argued, were ineffective under the provision brought about by Miller. Drugs and drug paraphernalia are easily disposed of and destroyed, so police require the element of surprise to seize them.

Soon after the Miller ruling came another Supreme Court case, Ker v. California, which amended the knock-and-announce law and allowed forcible entry by police in cases in which evidence might be destroyed. The Kers were a married couple whose home and car had been raided after George Ker was seen speaking to a suspected drug dealer, whose alleged criminal activities the police had failed to find evidence of. Law enforcement officers had entered the Ker home without a warrant and, upon seeing marijuana, had arrested them both.

During the Nixon administration, the scope of no-knock warrants was increased in response to concerns that drug dealers were too unpredictable and too dangerous to be granted warning before being raided. This law, however, was quickly and understandably repealed after being repeatedly abused by law enforcement.

Nevertheless, narcotics cases continued to define and refine the no-knock rule as time went on, only being revised to include dangerous circumstances with the 1997 Supreme Court Case, Richard v. Wisconsin. In Utah, no-knock warrants are only issued in cases involving drug possession, pointing again to the legislation’s deep-rooted connection to drug crime.

The majority of states permit no-knock search warrants at a judge’s discretion, while thirteen states allow the warrants in explicit terms. Only in Virginia, Tennessee, Florida, and Oregon, no-knock warrants are banned, although these restrictions do not apply to federal law enforcement.

No-Knock Raids on the Rise

The issuance and execution of no-knock warrants have steadily increased over time, despite the bans and restrictions in many states. Between 1,500 and 3,000 no-knock and quick-knock raids were executed in the early 1980s, when the warrants were first becoming “popular.” Since then, the number has doubled many times over, with the current estimates producing figures between 20,000 and 70,000 no-knock and quick-knock warrants issued each year in the United States. Most are issued looking for marijuana.

The Portrayal of No-Knock Warrants in Pop Culture

With their chilling frequency, it’s not surprising that no-knock and quick-knock raids are so popular in movies and TV shows. In cop shows, even “socially conscious” ones like Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, a no-knock raid is depicted as an act of heroism on the part of the police. Typically, the audience watches a SWAT team kick down some murderer’s door, just in time to save an innocent victim. Raids, these shows indicate, are just one-way justice gets done.

In reality, most no-knock warrants are served for drug-related offenses. The minority of these types of raids are inspired by homicide cases, though it was a murder investigation that precipitated the death of Amir Locke. All too often, no-knock warrants, issued in response to non-violent crimes, end more lives than they save.

The Grim Reality of a No-Knock Raid

Conducted in the early morning or at night, times statistically associated with a higher risk of error, the frenzied nature of these raids generates panic and confusion in civilians as well as in law enforcement officers. Adding to the deadly mayhem is the absence of regulation in many states regarding no-knock procedures. Officers are not required to wear uniforms when conducting a no-knock raid, which has resulted in the deaths of many plainclothes officers, who were believed to be intruders by homeowners and the execution of robberies, wherein thieves allege to be members of law enforcement. In one case, two members of the LAPD faked no-knock searches for the explicit purpose of robbing homes.

Though not easy, reforming police procedures is less difficult than reconciling no-knock policies with already hazardous state self-defense laws. “Stand-your-ground” laws permit would-be victims of crimes resulting in bodily harm to use deadly force against their attackers and exist, with some nuances, in 38 states. Castle laws, also known as castle doctrine or defense of habitation law, are more directly applicable to no-knock warrants, which almost always are issued for residences, and allow homeowners to use force to defend their “habitation”. With so many gun owners in the United States, it’s no wonder many no-knock warrants become violent. The defensive maneuvering of a scared civilian often gets them killed and others hurt.

However, there are too many deaths resulting from no-knock raids to blame fear and confusion for the bloodshed. Between 2010 and 2016, almost forty people died during the execution of no-knock warrants, while SWAT raids claimed over ninety lives during the same period. Most victims of homicide resulting from stand-your-ground laws are white men, whereas the majority of victims in no-knock raids are people of color, indicating prejudice plays a larger role in these deaths than state law and gun ownership.

The On-going Search for a Solution

Though many of the institutions perpetuating the violence carried out by no-knock warrants are too large and complex to be dismantled here, there are important steps to be taken to reduce further harm. Some can be accomplished easily and are as simple as executing warrants during the day and doing so in uniform. Other solutions include the switch from no-knock to quick-knock warrants, requiring officers to announce their presence and then wait 30 seconds before entering a property. This time period may allow the occupants of a space enough time to register a police presence, mitigating fear and confusion while not permitting them enough time to dispose of potential evidence. These reforms, however, don’t stand to eliminate the problem, nor do they attempt to address the deeper social and cultural ills at the heart of the issue.

The failures of no-knock warrants largely reflect the failures and hypocrisy of America itself. That people should die during the seizure of marijuana, one of the most common targets of these raids and a drug already legalized in 18 states, is ridiculous and sad, but far sadder is a simple fact that drug use has been demonized longer and far more vehemently than racism ever has.

While the question of what to do about no-knock warrants has been circulating in the mainstream media since the 1990s, there is still no clear answer. But maybe that’s because it’s the wrong question, a question that ignores the people and the systems behind the trigger. No-knock warrants are a problem in a constellation of others. The confusion and fear they generate cause people to act on their implicit biases, making decisions in ten seconds that they might not have had they waited for ten more. Maybe ten seconds more would have been the difference between life and death for Amir Locke.

Further Research

Organizations like End All No Knock are part of the effort to end this practice. Learn more about the statistics and join the campaign at endallnoknocks.org.