Aspen Matis’s memoir, GIRL IN THE WOODS, chronicles a five-month trek that was ambitious, dangerous, and transformative.Four months into her solo-hike, at a small-town library in a river valley in the Oregon pinewoods, Matis met a man named Dash. He was also walking from Mexico toward Canada, also tracing the Pacific Crest Trail: the identical route. For the past four months, the pair had been within a few days’ walk of each other, trekking northward in near-perfect sync.This excerpt begins in the midst of Matis’s first night in a hotel room with this fellow drifter — the man who would become her husband:

His eyes were lit with intent curiosity as he waited for my words, as if he wanted to find in me someone worth loving.I didn’t want to tell him anything that would ever kill it.And so instead of answering, instead of telling him about my rape, I evaded his questions about my history and told him with enthusiasm that, more than anything, I loved to write. I was reading THE BEST AMERICAN SHORT STORIES 2008. I showed it to him. I told him I was walking because I just wanted to have an adventure.

He asked if any of the stories were good. I said, “Most of them.”“What’s the best one?”

“Galatea.”

I told him about my favorite story. It was about a girl who went to Cornell in Ithaca, New York, to the same school Dash had gone to. She married a hermit who lived in the town but didn’t go to the school or work, though he called himself an inventor. She was devoted to him. Each time I read it, I wanted things to work out, for their weird intense hermit love to last forever. But it doesn’t. They end. I reread and reread and reread the ending, always in denial. I hoped that I could find where they could have salvaged it, the mistake she had made that caused him to leave and see how they could have saved their marriage, what tiny thing she could have done to make it last forever, as intensely as it was in the beginning. But one day the husband disappeared and went into the woods and didn’t come back.I must’ve fallen back asleep; I woke to Dash reading. He lay close to me, focused, the book propped open on his pillow. I watched morning sun rest on his hand as it turned a page.

It felt impossibly natural waking to him next to me, so much safer than I’d felt even the night before. I parted my lips, wanting on that fresh morning to finally tell him about my mother dressing me and years of feeling ugly. About hating my body. About my rape and hating my body even more. I wanted him to tell me that my mother had reacted to my rape without compassion, that she was wrong that I was damaged, my school was wrong that it was my fault — my rapist was wrong.He was still reading, he didn’t see I was awake. I said, “It makes me really happy you’re reading the stories that I like.”

He looked up at me. He said, “And then, you can tell me why they’re good.”

He was smart, charming. He wanted to know my opinions. He needed to know what I thought, wanted my ideas. We were impressed by each other.

I realized we had so much in common — not only because we had literally physically lived our last four months covering the identical terrain — but by virtue of the fact that we had chosen to. We were caught up, could walk the last 500 miles together. Miraculously both walking this trail, on the same mile, at the identical place.

I wished I were able to remain entirely myself with him – to be fully honest, to expose my history and shame — for him to know, and to still want me with him.

But I didn’t tell him.From my hotel window, I could see Washington. I wanted to enter the state ahead, together.I didn’t tell him.He turned the book to show me the story he was reading. “Galatea.”I didn’t tell him.We reawakened to hooting — a pack of voices, cheering. Magically, we stepped out in daylight into a celebration. Along the river people were setting up square green canopies, hammering support cords into the dirt. Thru-hikers of all appearances pitched their tents on the grass along the riverbank. I felt the energy — hikers flocking from all around, hitchhiking back south from all points north on the trail, hopping out at the Columbia’s bank for tonight’s party. We discovered that we were here in Cascade Locks on Trail Days, the annual celebration for all the hikers who had made it this far on their PCT journeys. Trail Days would be a giant hiker-party, much like Kickoff.

We decided we would stay in Cascade Locks another day together for the party. He also wanted to be with everyone else. I pitched my tent under a tree, my temporary shelter. Dash didn’t pitch his. Our tent was one of hundreds on the big green under tall pines along the river. We’d both heard of the party and always hoped to attend — and here we were on the morning of it. Dash and I happened by our great, good luck to be in Cascade Locks, no need to hitch back. As afternoon light brightened, a raffle was beginning.

Gear and clothing companies gave away tents and sleeping pads, socks, the things hikers needed. Groups convened, quirky characters I’d heard about: the lost boys who hike the trail every year; the “trail celebrities” who set speed records hiking the PCT in just eighty days; the trail legends who had hiked the PCT in its earliest years, half a century ago. Two thousand people filled the green along the Columbia River. Last night it had been quiet.Someone had set up a projector to play onto a sheet in the woods, and a younger mass of hikers was dancing. Sunlight cupped in the river’s dimples, shimmering; feet twisted on grass slick with red-brown pine needles, the sky a fierce blue. I was a part of this euphoric celebration of the distances our legs carried us, of making it.

We gathered here to say goodbye before bursting northwards and finally reaching Canada, proud we’d made it to Washington State. We were high on the anticipation of the final stretch. The raffle began — two bearded M.C.s with mics calling out trail names, their booming voices quick like giddy kids.Dash bought forty dollars worth of raffle tickets for hiking gear.

He was giving them all away to people — ten to a one-eyed ex-con named Yogi Beer; ten to me.I won a Neo Air, the Cadillac of sleeping pads. It was worth $200 and ultra light. Yogi Beer won an Osprey backpack. Dash won a daypack, the smallest prize among us, yet he seemed completely happy.I couldn’t believe our small group’s luck. I couldn’t believe my luck.Together Dash and I wandered past the concrete state park bathrooms, along the river cradling sunlight like pools of gold. My tent was olive green, for two people. It was at our feet.Wordlessly, Dash climbed in. Camping by the gorgeous border-river, together we disappeared from the big party that we were so perfectly paced for.

He carefully undressed me, exposing the striking whiteness of my stomach, my pale shoulders tinted pallid by sunlight filtered through the green tent walls. Those first intimacies with him were different than those with others I’d known. There was no vulgarity. My body unclenched in his hands, warm and calm. Touched by his lips, how different the things I now wanted were — bigger, they felt limitless, because his warm touch made my nerves finally dissolve into trust.In the tent next to us a young, muscular guy named Buddha, one of The Thirty Eights, was fending off an old woman called Sugar Mama. “You must be cold,” she said to him, drunk. “Come into my Volkswagon.”

“No thanks,” he would say politely, always softly.

Dash and I kept cracking up. Buddha heard us too.

We were still again, lying facing each other. I was euphoric, studying his relaxed lips. I asked him if we had just had sex.“What?” He smirked, confused.“Was that sex?” I asked him. Everything had felt so good, so easy — like I imaged sex should — that I actually wasn’t sure.His lips were smiling now, his eyes were bright with tender laughter. “We haven’t yet,” he said.The Trail Days celebration was raging and for once I was in the heart of the thru-hiking body. I was surrounded by people who’d chosen to be homeless for five months, to have stones in their shoes, to sleep on strangers’ lawns or just on roots, constantly filthy. All these strangers bonded in the choice to take the cards they were dealt and toss them in the dirt. I had come to see: we all had reasons.But for now we were in a quiet center. In our tent. The party pulsed around us, but we spent hours inside making out, invisible, the eye of our own storm. We stayed at our spot under the tree beside the Columbia for three days, three exciting nights, sexless.

The verdant town of Trout Lake was dotted with white llamas, they wandered the endless fields of huckleberries. Men in the fields picked them, filling up white buckets. Pounds of berries sat on the general store floor. The gas station sold the World’s Greatest Huckleberry Milkshake, and so did the coffee shop across the road, too.The town's small hotel was full, and the motel was full. The woman at the general store wherein everything except huckleberries was exceptionally expensive told us that an L.A. entrepreneur who'd become a Buddhist monk opened a monastery in town, and he sometimes let hikers sleep there. She called him for us. In fifteen minutes, he pulled up in a shiny new white Escalade.

We rolled past more huckleberry fields, more men picking, the hills beyond them golden with sun, it was beautiful.That afternoon, we sat in silence at meditation in the temple, and then climbed spiraled stairs to our bedroom. We made love, even though I was on my period, and, rolling over each other, we imprinted the white linen sheets with blood.Dash spot-cleaned the sheets with bleach as I walked with the monk, picking snap peas and cauliflowers from the monastery's organic garden to cook for our dinner. After we ate, Dash and I began to wash dishes together; I confessed I’d never actually done dishes before. My face heated, I feared he’d see me as a child. The water was steaming, Dash was running it. He smiled, told me, “I picked you underripe.” That night we did the dishes together.

Descending a ridge one chilly morning, Dash told me a true story about the tropic ex-pat phenomenon: young men who move to Thailand and live off the money they've already made for the rest of their lives. In Thailand they're rich enough to have a girl wash their bodies for them as they shower on the beach. Massages cost only one US dollar.

I wondered what he was telling me in this story. I asked, "That's what you want to do?"Their brains get squishy," he said. He grinned dopily. "They rot." He switched topics and told me instead about the work he had done in finance in New York City. He’d been paid a lot of money to calculate the probability of different natural disasters and estimate the value of insurance against them.He then said that really he was more interested in what I wanted to do. He wanted to show me the hidden swimming holes in the river gorges of Ithaca, in upstate New York where he’d studied math. He wanted to take me to the glaciers in Waterton National Park on the Great Divide Trail in Canada, he told me it was “more beautiful than the American side.” The American side was Glacier National Park — revered for its beauty. We’d roadtrip up there, it was too stunning a place to look at alone. He wanted to tell me everything he’d figured out, show me all the beautiful places he’d found. We talked about places we might go together at the end of September. We spoke without ever asking if going together was what the other wanted; it was.

I told him of Colorado, where I lived before the trail, below the mountains there: red clay and the smell the dank river mud, and of thunderstorms: dust rising. Pikes Peak snow-faded like a permanent ivory castle. Together we’d ski it. He had ski-raced at Cornell. With him, I’d be fearless.He seemed intrigued and excited.He told me he had always wanted to live in Colorado — Co-lo-rado.

I thought it was lucky that I’d lived somewhere he always wanted to go. Anywhere I went with Dash would be good, because I would be with him. And really I still loved Colorado Springs. I had always loved the beauty, I didn't forget my childhood memories. The Bluffs, the red rock dirt; I couldn't think of anyplace better to go: I could return, even alone. I understood: I could. It couldn’t be bad this time, I was immune.

I wouldn’t run away from that pain, the rape. I was done running. I felt tremendous. My rapist felt like the outsider. He didn't seem to belong with my memories of the Springs, he seemed disconnected from Colorado. I understood now that he could have been anywhere, he didn't taint the state. I had nothing to run from. Really I still loved Colorado Springs. It was my childhood Eden, nothing could kill that love.And for the first time on the trail, I began to feel excited to return to my life off the PCT. I would return to Colorado Springs — with Dash. I saw that I was still in love with it. I grinned at the thought of kissing in winter’s cold light in our spare apartment, cloudlight resting on the wooden floorboards, a snowstorm whiting out the world outside. High on the North American Continent’s continental divide, living inside our glass-walled box of home.I began to lust after our conjoining life.

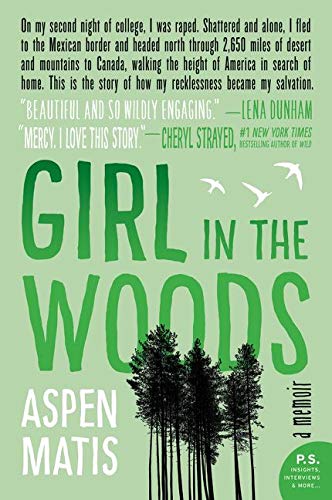

Finishing the journey we’d independently embarked on, we reached Canada together. I would marry Dash.I went back to college at The New School — and then sold GIRL IN THE WOODS, unwritten, to HarperCollins.Dash would leave me, return to the woods, and walk from Mexico to Canada again. He wouldn’t come back In his absence, I remained in our apartment in New York and finished our story, my book, writing about falling in love with Dash while I was missing him, once again alone.It was surreal, I hated it, but I didn’t stop. Instead, I grew in the space his absence left.