BY DX21 Dasun

There was a time when aboriginal societies would listen to nature, commune with trees and seas and converse with cats, caterpillars and chameleons. But now the soils of savannahs, the grasses of Great Plains and the thickets of forests are replaced by asphalt, concrete jungles, and brick and mortar experiments known as housing projects. The city-dwelling descendants of the aboriginals chat with cats in cyberspace; cats that used to be hip to jazz but now they rock and roll with reservoir road dogs trapped in “trap” who kill at will to “drill.” They won’t hesitate to sic the wolves on you; not realizing their rap renditions are transitions of timeless traditions.

There are some who see the connection between Hiphop and the ancient cultures of its creators; the pulsating energies of native spirituality, West African mysticism and infusions of Eastern teachings. Thing is, today’s downloads have little to do with deliberate vision quests. The rituals rarely recognize reaffirmations of relations to righteous realms. The hiphoppas listen to different types of streams than the babbling brooks of their ancestors. Jay-Z said the streets are watching, but what’s more, if you listen, the streets talk and the streets are teaching. But living in Bob’s Babylon, it’s hard to see what the sidewalks have to say of the spirit.

Old Man Streets has prowled and pounded Harlem’s pavement since it was strewn in the 60’s with shattered glass and syringes. A ‘street scientist’ for around a half a century, he has spent over two decades as a cultural critic and political correspondent with the community press. “Music has always been spiritual,” says Streets. “The magic word in spiritual is ‘ritual.’ What’s more ritual than music?”

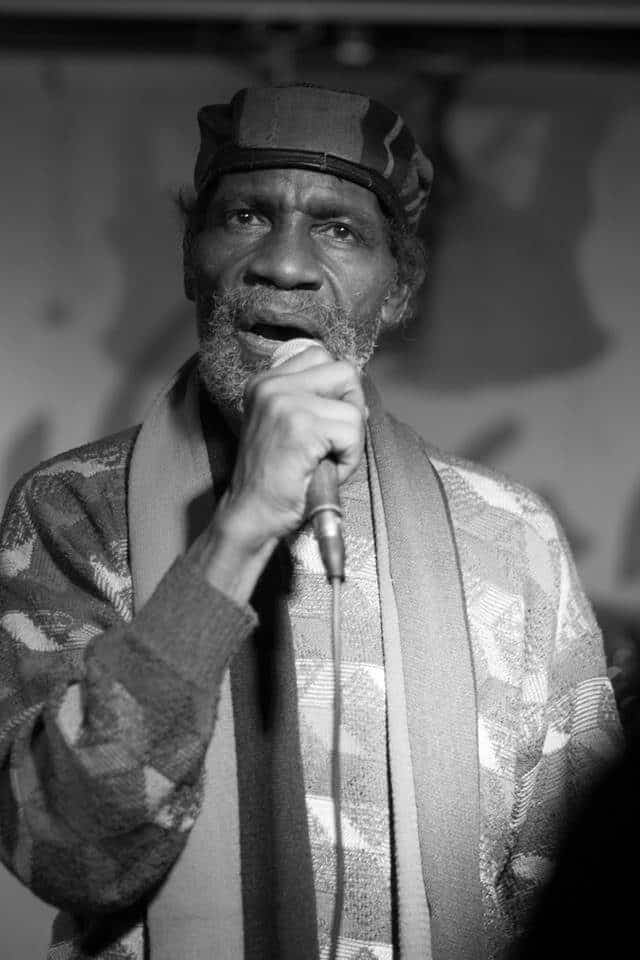

Abiodun by Poetic Life Photography

Spirituality has many names with the realm of Hiphop culture, whether it’s called being ‘woke,’ consciousness or cultural awareness; it’s alluding to the same phenomenon. And while Judeo-Christian traditions are always prevalent within the ethos, in this context, spirituality is being referenced outside of that frame. “I think that anything black people create, there is always going to be a connection to spirituality, because we are spiritual people, even if we don’t want to claim that; that’s who we are,” says Abiodun Oyewole of The Last Poets. The legendary and revolutionary artist collective is recognized as the ultimate forerunner, precursor and foundational element of Hiphop’s linguistics.

“Every living thing has a beat, a pulsation of some kind, and hip hop amplifies that beat in a big way so that it becomes dominant, and then you ride words over the top of the beat,” says Oyewole. “When you’re dealing with that type of thing, that’s a call to Africa in many ways. Many of our hip hop artists probably don’t realize that, but that beat is a sound calling out to Africa, and they’re riding the waves to go back home. I don’t know if many of them have made that connection, but that is the direct connection.”

Author, artist and activist, Supa Nova Slom, the Hiphop Medicine Man; a student and teacher of Kemetic and Native American sciences, sees even deeper into the dark waters within the veil.

The son of renowned holistic healer and Kemetic priestess, Queen Afua, Slom has long been entrenched in the ancient teachings and makes many correlations. “If you was a graffiti writer in an ancient Kemet (Egypt) you were writing hieroglyphs, you were writing on the walls. So we’ve always had tagging on the walls—man has been tagging walls since man came on the planet,” says Slom. “And then we had the stewards of sound—the DJs, the beat-maker, the drum-maker. And then you have the [djali] (the griot in French): the orator, the MC. And then you have the breakers, the ones who would do the ceremonial dance. So you have all these tenets and all these elements. And then you had the fifth personality, the one that had the knowledge of the Godhead that would tie everybody together.”

Abiodun Guerrilla Republik

Slom links hand signs prevalent in Hiphop street culture to the ritualistic poses of yoga’s tantric mudras. He speaks of relations between dancing in the streets and dances seen at Native American pow-wows among other connections. “We can go to Kenya, we can go to the Congo and Zululand. We can see how they would use the drum, and they would chant to the drum in masses,” says Slom. “They’d form a cypher, and perform in a circle and kind of like how you have breaking. Then you’d have folks dancing and folks chanting, chanting the dances on, kind of like how we would get into a cypher. We would chant back and forth to raise the energy.”

While the cypher may historically descend from ancient sacred circles of chant, dance and drum, in Hiphop, it is directly influenced by the “knowledge of self” consciousness of The Nation of Gods and Earths, commonly known as Five Percenters. ‘Cypher’ is a corruption of the Five Percenter term ‘cipher,’ which has many meanings within God and Earth society.

“Getting in the cipher? What do you think the cipher was?” says Streets, one of many longtime advisors to Nation of Gods and Earths members. “The cipher ain’t nothing but what Gods was doing; getting in the cipher dropping bombs on each other… they [just] started doing it musically.”

It was through the street corner, rooftop and playground ciphers that the Gods and Earths spread their teachings; the ciphers culminating in their monthly meeting, the Universal Parliament. This whirlwind of street science swept through New York City and was deeply embedded in the youth culture during the same period as the genesis of Hiphop. This cross-pollination influenced the international Hiphop society of The Zulu Nation and eventually impacted the culture directly through acts such as Rakim, Big Daddy Kane, Poor Righteous Teachers, Brand Nubian, Nas, Wu-Tang Clan, Erykah Badu and countless others.

Brand Nubian’s Lord Jamar presents an understanding of Hiphop’s spirituality shaped by decades of Five Percenter study. “I would label it as ‘rolling with your true self;’ rolling with more of your higher self than your lower self,” says Jamar. “Going with that intuition of who you really are, rather than who society tells you you are. We knew we were kings and queens. These mothaph*ckas were trying to tell us different, and through hip hop we were able to tap into our spiritual side regardless of what society was trying to say we were. “

Slom passionately asserts the debt Hiphop owes the Gods and Earths, even suggesting that rappers give five percent of their income to build a Five Percenter learning institution in Harlem. Even a writer was exposed through Hiphop to the Nation of Gods and Earths and to Dancehall, which ultimately led to the discovery of Rastafari. The spirit rituals of music and culture are very powerful. “If you ever look at the Universal Parliament and how the Gods [and Earths] got up and expressed themselves,” says Streets. “That was a whole new thing.” A thing Streets and many others say are at the foundation of Hiphop.

Artist, cultural icon and Hiphop purveyor and tastemaker Fab Five Freddy concurs. “It was an organic development primarily because the Five Percent had such a strong spiritual urban connection to some of the most dynamic brothers and sisters on the street,” says Freddy. “That goes back to the 60’s, but mid-80’s into early 90’s as Hiphop shifted into high gear, many of the leading rappers were a part of the Five Percent Nation and infused their rhymes with those ideas, ideologies and that dynamic way of speaking and also thinking.”

That ‘whole new thing’ Streets spoke of was often at odds with the traditional Judeo-Christian spirituality of the American mainstream; one that many in the Hiphop world found historically oppressive. Streets sees a conflict akin to a Neil Gaiman novel with the ‘Old Gods” of the Judeo-Christian elite in opposition to the ‘New Gods’ of Hiphop. “We’ve been creating it; they’ve been controlling it… That’s why it’s so hard to put out a conscious record,” says Streets. “You see how they hushed the real God of rap, Rakim. Eminem and all the ones they praise, praise him, but they can’t praise him because he says he’s God and he’s going to say the Blackman is God… How come he never got a Grammy?”

Blue Pill via YouTube

But was it really a new thing or just a continuation of what always was? It is compelling to note that Oyewole, a Hiphop forefather whose fingers help fashion the aesthetic, is a practitioner of Ifa, the West African science permeating Yoruba, Santeria, Candomble, Vodou and many other historical and Neo-African mystical practices. Whether conscious or unconscious, this strong undercurrent flows within Hiphop culture as West African people are the primary African element of African-American ancestry. “Many of us are not aware, but in all things, yes, Ifa has a lot to do with us,” says Oyewole. “The majority of the Africans who they tried to make slaves… the majority of the people who they captured, apprehended, and put on those boats came from… the places that were practicing Yoruba.”

Oyewole sees Ifa running rampant in Hiphop. “When you start dealing with beats and rhythms, you’re dealing with the whole African tradition, and of course there is no greater tradition than dealing with the Orishas, those big personalities, “says Oyewole. “I can look at Biggie and I can look at Tupac and I can see Obatala and I can see Shango. I can look at Queen Latifah and see Yemoja. I can look at Foxy Brown and see Oshun.” It the ability to see his people in the Orishas that attracted Oyewole to Ifa in the first place. “They had Gods that reflected the personalities of people who I actually knew—and I could recognize those Gods walking the street. Now many people don’t recognize them because we are not taught that. We’re Christian, we’re into this Christianity and we try to make Jesus work for everything and Jesus is just one of the Gods, he’s not all of them,” says Oyewole. “We are a multi-god people, and they all have a place and should all be respected.”

Streets, Freddy and Oyewole all say that the tradition of toasting, telling streets tales in rhyme, played a part in the verbal pugilism of rap. Jalal Mansur Nuriddin of The Last Poets’ 1973 rendition of the traditional toast, “Hustlers’ Convention,” is considered a watershed moment in Hiphop’s evolution. Toasting itself is connected to the djali; the historical and spiritual repository of information in West African culture. Some sources seek to categorize toasting (the chanting of a Dancehall Deejay) in Jamaican Reggae as being different or distinct from African-American toasting rather than recognizing their commonality in the djali; with variations being geographical. It is such compartmentalization, mainly due to marketing considerations, that helps to keep the current manifestations of mystical music and mythmaking cut off from, and without the explicit contextualization of, its cultural root.

Abiodun By Vagabond Alexander Beaumont

As the djali perpetuated (and continues to perpetuate) the cultural content and context needed to maintain and advance African societies; for better or worse, the rapper holds a similar role in modern day. “We see how the knowledge of the [djali], the storyteller, how that also was a theme in the native traditions and African traditions,” says Slom. “[So too,] we see how the MC’s story tell, and tell us of their surroundings, about legends, [and] about the people that came before them.”

While thanks to strong connections to Rastafari, Reggae has retained a regal amount of the spirit ritual; rap has been sapped of a lot of its mysticism. At one time or another, even teachings such as Buddhism and Hinduism have made their way into the music and culture. Slom talks of how many schools of thought were united in Hiphop such as the Moorish Science Temple, The Nation of Islam, the Nuwabian/Ansar Allah community, the Black Hebrew Israelites currently influencing stars such as Kendrick Lamar and Kodak Black; and even Rastafari.

Some blame a decline of influence from societies such as these and The Nation of Gods and Earths as proportional to the decline of spirituality in Hiphop. Streets disputes this as a mischaracterization: “It was a business decision that made the music go that way, not lack of the Five Percenters. We make the music. We don’t control it. They’re in the meeting room with long tables just like that scene in The Godfather when they said, ‘We’re going to give the drugs to the darkies, they’re animals anyway…’ The powers that be didn’t want to hear all that sh*t about how [they] killed the Indians and how [they] enslaved the Blackman and, even now, how the cops are shooting mothaph*ckas down in the streets. So the money was taken out of that genre.”

At one time Hiphop was dominated by consciousness, but the paradigm shifted. “As eras and styles of music evolved, then that Islamic-inspired Five Percenter thing became strong in Hiphop and it had a nice little run,” says Freddy. “But artists and styles emerge and artists want to talk about different things.” While Oyewole speaks of the synergies of spiritual traditions, some see oppositions and conflicts. “It was the Judeo-Christian visionaries who put mothaph*ckas out like Biggie. Biggie turned the wheel. So rap swerved away from consciousness to money.”

It’s poignantly poetic to point out that The Notorious B.I.G.’s first single appropriated the penultimate lines of Oyewole’s classic recording with The Last Poets; “When the Revolution Comes.” Where the Last Poet ended his piece is where Biggie Smalls began. “There was a big part of me that was hurt that it was misused because it was something that I was saying that we should not do, because we should really be preparing for revolution,’ says Oyewole. “To hear that—I didn’t realize that Biggie was the first one, but I knew it was being used a lot by different rap groups—I was just very hurt that people would take what I had said and turn it inside out and actually use it as a chant.”

But even without corporate control, just as most spirituality deals in duality, so too Hiphop is a double-edged sword even if left to its own devices. It can free the mental with instrumentals or make slaves with sub-bass. “We’re doing some God music,” says Jamar, “but we f*ck it up with lower vibrations and themes and sh*t.” Ignorance could be a dangerous bliss as Hiphoppas may be summoning powers and entities without having an understanding of them. Blue Pill, the visionary scholar, online entity, and one of the Twin Pillars of “the conscious community” has extensively lectured on the impact of certain frequencies found in rap music.

Blue Pill by Christiana Dah

“[Musical elements like] 808 and boom bap; these would be considered war drums, four fours and military war rhythmic syncopations,” says Pill. “It gets you ready and prepared for trance for war. I would say that it has worked in our benefit and to our detriment because when you are channeling war spirits; those spirits have names. So the fact that we have the drums without the direct calling upon said entity, it has worked to our detriment because we have called forth these particular entities without knowing their names and giving them any direction.”

Blue Pill talks of other elements that have become prevalent in Hiphop. “Little less than a decade ago we were having an open conversation in Hiphop about the presence of, for lack of a better term, satanic forces, you know by way of the Illuminati,” says Pill. “The conversation somewhat hit a crescendo in about [2009] or [2010] with the release of The Blueprint III with Jay-Z. And people were having this conversation in Hiphop, the education pretty much wasn’t all the way, this was coming out of (the documentary films) Loose Change, Zeitgeist, these different introductory series to people that somewhat gave them the understanding that them seeing the all-eye seeing pyramid was the devil or a particular hand signal. It was more so about the symbolism than anything else. And then it proliferated. It became something that the culture actually adopted and embraced. And then now we’re in a place where the Lil Uzi Verts of the world or the Trippie Redds of the world, or different young artists are openly saying that ‘I’m a devil worshipper and this is the team that I’m riding with.’”

But all is not in dire despair, in contemporary culture, Kendrick Lamar, J. Cole and even Chance the Rapper are mentioned as new luminaries. 21 Savage is a known follower of Ifa traditions. Spirituality remains but just not as dominant. “I think it still exists. You’ll still hear certain artists, but it’s not as permanent and mainstream and in-your-face as it was back then. You have to search for these types of messages and individuals,” says Jamar. “You can never destroy it, you can just try to cover it up; whatever. You can try to bury it, but it’s always going to unmask itself in different ways. Even in the ones that you think are negative. Certain things about how they move people is spiritual, even if they’re trying to cover it up.”

Blue Pill thinks it is a matter of the mindsets making waves in the digital age. “Everything is about time keeping; our ancient ways was always about tracking the cycles of time. With that being said, said disciplines have to know that they have to be in line with the times. The Nation of Islam is going to be here because they have a youth movement, shout out to Brother Ben X and Brother Rizza Islam and other members of the [Nation of Islam] that are youthful; that got a grasp of social media and have a digital footprint in that world.”

Jamar for his part, does the work of unveiling with his “Yanadameen Godcast” show. Blue Pill, along with his twin brother and pillar, Red Pill, lectures relentlessly, promotes powerful messages and imagery in their fashion line, Kingz Kounty, and has an enormous body of scholarship in the digital realm. Slom publishes books, instructs incessantly and is releasing his latest studio album, Love in the Midst of Chaos. Freddy never rests from sparking art. Oyweole and The Last Poets still travel the world shining enlightening lights and Streets continues to teach.

“Kids who go to Hiphop concerts are moved by the spirit of the music, the sound, and the rhythm. They might be saying something that’s got nothing to do with something that’s gonna lift them up, but the spirit of it all is the sound,” says Oyewole. “It embraces you, and causes you to move; you just can’t stand still, you’ve got to move your body, you’ve got to get into the flow of it all, because it’s a dominant feeling. It’s the voice of God, and you can’t avoid that.”

With the spirit, it is truly a circle, the cipher, 360 degrees with no beginning or ending; what goes around comes back around again. “Africa is going to be with us and we’re spiritually motivated in everything we do,” says Oyewole. “That’s never going to stop. It’s Africa calling.”