On July 6 2020, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement announced that international students who take classes entirely online in the coming fall semester would be barred from the country. Although ICE rescinded the policy shortly after intense backlash from universities, the rule is just a symptom of the larger difficulties that international students face on a regular basis.

As the U.S. rides the first wave of the pandemic, student visa holders are subject to infinite limitations and uncertainties now more than ever.

Why the ICE Announcement Still Matters

Although the ICE policy was widely interpreted as part of efforts by the Trump administration to reopen schools in the fall rather than a targeted attack on the international student body, such broad strokes showed no regard to the health of foreign students and what they have to grapple with in a global pandemic. Pursuing a PhD degree in Economics at Stanford University, Lily has been quarantining in the school dorm in hopes of riding out the pandemic. When the ICE policy came out, she had no choice but to register for more in-person classes. “I feel very insecure about my health, education, and my immigration status…This ICE announcement hurts international students as well as the whole school, and it puts the health of faculty, staff, and students under great risk,” she said.

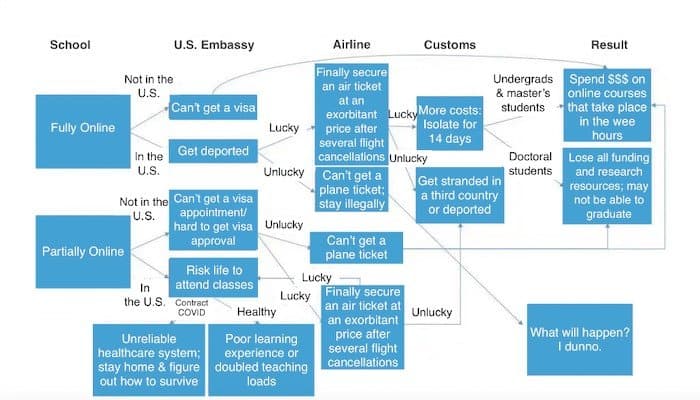

More than a million international students come to the United States every year, each of whom faced a uniquely challenging situation under the ICE policy. Yiyan Zhang, a PhD candidate in the College of Communication at Boston University, created a flowchart explaining what the ICE announcement entailed for foreign students. Amid all the confusion, international students needed to shoulder physical, financial, and immigration risks as well as the possibility of not getting their degrees.

Even without being enforced, the ICE rules confirm and intensify the deep-seated insecurities of student visa holders, who already stand on shaky ground. “The new policy makes it clear that international students are not welcome in the US…Even if we do nothing wrong, there’s a possibility that our already-precarious status will be canceled one day,” an anonymous student told Politico.

Stephanie Schwartz, an assistant professor in the University of Southern California’s department of political science and international relations, further elaborated on the long term harm the ICE policy causes. “The consequences of the announcement endure regardless…People are scared and have been caused immeasurable pain just by the announcement and what it could mean for their lives now and potential future visa status. The constant vigilance and worry take a severe toll,” she tweeted.

It is also worth noting that while the ICE policy seemed strict, it was generally a reiteration of pre-pandemic rules in place that international students had to follow all along, which pose significant constraints on how they are allowed to plan their academic life. The rules stress that to keep their status legal and valid, student visa holders must register for full-time every fall and spring semester, and only one online course may count towards full-time enrollment. For those who wish to enroll part-time, they must obtain permission from the school for reasons such as having a medical condition or being in their last semester.

Challenges for International Students Who Work in the US after Graduation

OPT: Application Process, History, and Restrictions

In addition to international students who are still working towards their degrees, a large number of foreign students in the U.S. have graduated and are entering the workforce. International students must first jump through time-consuming legal hurdles to obtain eligibility to work – preparing onerous legal documents to apply for Optional Practical Training (OPT) as early as 90 days before graduation and pay a $410 application fee. In the 2018 – 2019 academic year alone, more than 223,000 new graduates remained in the U.S. to work under OPT.

OPT refers to Optional Practical Training that is within the student’s major field of study. Historically, the U.S. government has allowed foreign students to engage with some form of OPT since 1947. In 1991, the Office of the Federal Register made it clear that post-completion practical training is limited to no more than 12 months. Subsequently, major reforms came in 2008 and 2016, allowing international students with degrees in STEM fields to extend their one-year OPT period by 24 months.

Although OPT grants eligibility to work in the U.S., it also poses significant limitations. During the one-year OPT period, foreign students have a maximum of 90 unemployment days to find a job that is directly related to their major of study. In addition, the rules also stipulate that international students cannot start working until they receive approval of OPT in the form of an Employment Authorization Document (EAD). In other words, OPT constrains the types of jobs foreign students can do and floats an uncertain start date, both of which make the job search process much harder. In Canada, another popular destination for international students, students who graduated from a program that lasted two years or more may be eligible for three years of Post-Graduate Work Permit, during which no unemployment days will be counted.

Jennifer, an F-1 student visa holder from China, graduated from Boston University in winter 2019. “I couldn’t start working on OPT without getting my EAD card in the mail. My offer almost got cancelled because I had to delay my start date multiple times waiting for my EAD card to arrive,” she said.

As difficult as it is to find a job using OPT, the pandemic has made the situation murkier. While being on OPT, Walton Wang lost his internship with a New York cosmetics company around April, and he believed he could easily be jobless for three months. Although he always wished to stay in the US, Wang changed his mind after observing how the U.S. government handles the pandemic and rising racism and violence against Asians in the country.

However, as the number of flights between the U.S. and China dwindled and the price of flight tickets skyrocketed, the hope of returning to China was also dim. “I have no way of returning to China, and I can’t stay here for long. I have nowhere to go,” Wang told CNN.

In the pre-pandemic era, student visa holders had always been subject to extensive legal requirements and limitations both in and outside of school. It is unrealistic and sometimes inhumane to expect international students to adhere to the rules meticulously as they navigate a global pandemic in a foreign country.

H-1B Work Visa: Application Process and Struggles

For international students who wish to reside in the U.S. in the long term, many resort to employment-based immigration, using OPT as a stepping stone to apply for an H-1B work visa and later permanent residency.

To apply for H-1B, nonimmigrant workers must first find an employer who is willing to sponsor them and file the application. “Some people would hang up the phone the moment you said you need sponsorship,” Peng Yuhang, an electrical engineering student, told NPR. However, finding sponsorship is only the first step. Each year, there is a cap of 65,000 new H-1B visas in the U.S. Due to the fact that there are far more applicants, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) instituted a “lottery” system for accepting applications. Quartz reports that roughly 42% of applicants are selected through the lottery, and those who are selected still face scrutiny from USCIS for more materials and possible rejections, a situation that’s been intensified following Trump’s executive order in 2017 aiming to protect U.S. workers from foreign competition.

Many H-1B visa holders hope to obtain permanent residency by applying for employment-based immigration, but the lines are particularly long for foreign workers from India and China, who make up the majority of H-1B workers in the U.S. Particularly, for Indian nationals waiting for employment-based green cards, the backlog is so acute that those who apply can wait up to 50 years. “I will die before I get my green card,” Varun Soundararajan, a senior software engineer who works at Google, told Los Angeles Times.

While it was a win when ICE backed down from implementing the student ban, uncertainties persist for international students in the U.S. who try to fulfill their academic and career goals while treading on precarious legal ground. In 2018 alone, international students contributed $45 billion to the U.S. economy. More importantly, foreign students bring more diverse perspectives into American classrooms and make significant research advancements. It is about time that U.S. policymakers recognize the value of international students as well as the overwhelming legal pressure they must bear on a daily basis, especially during times like these.